In 1908, exactly four hundred years after the birth of Andrea di Piero della Gondola (Palladio) an Austrian architect traced another arc of a circle over the path that history walks on. That architect was Adolf Loos. The meaning of Nietzsche’s second of the four “Untimely Meditations” (Nietzsche 1874) the prophetic words of “Ornament and Crime” (Loos 1908) and Guy Debord’s concept of the image as the ultimate form of reification (Debord 1967) inevitably reunite in a circle that closes on itself with the dazzling agenda of an hedonistic sustainable development.

Excerpt from: “Dal Palladio al sacco di Baghdad”.

[…] Architecture, with the decline of hopes on the modern condition, in a state of subjugation to invariant synergies of politics and economics, falls short to bring about social reforms.

The ancient concept of Techne, that once held together manual dexterity and technical knowledge by reason of a role and a status awarded to the artist, did not have to make a distinction between fields of knowledge. That role declined and came to an end with the industrial revolution via the École des Beaux-Arts and the École nationale des Ponts et chausses, but not as a function and a need for representation. There is only an aesthetical version remaining about Architecture. Architects are nothing but the organizers of an hedonistic seduction. Once a magician, architect, and high priest of the Pharaoh, the postmodern Imhotep is still officiating the art ritual, sometimes not yet freed from his own autobiographical turbulent tide. It is precisely there that it breaks when reaching the shore, to the safe beach of official art, everything being pushed by the wave of democratization.

Even Richard Buckminster Fuller, while keeping himself distant from the aesthet-ism of the modern movement, believed that good design could promote and induce social reforms. Fuller, starting from his various attempts of Dimaxion prefabricated houses, working outside of the Vitruvian triad, criticized the styling behind which resided modernism and International

style’s similar interest towards prefabrication — but with a completely different sense than he had intended — with their aesthetic of simple shapes and square lines, taut in appearance to render the shapes of mechanized manufacturing. He totally rejected a way to build that simulated only from the results the ways and processes of industrial production.

People or public entities, who may be willing to pay for the services of an architect, do not understand or do not expect a “Good Samaritan” declaration of intent on the basis of passion, sense of justice and accountability, which are essential for us as humans (before being

architects). They may also have difficulty to understand it completely in a not-profit relationship between architect-user. They are not quite ready to embrace that in a society with its silent proclamation of the “survival of the fittest.” They therefore tend instead, to look at the architect persona essentially through stereotypes. One of the most popular, supplanting long

gone heroes like the one of Howard Roarke in Ayn Rand’s novel “The Fountainhead”, is the architect that can stimulate entrepreneurship within a dazzling scheme of hedonistic sustainable development. It is the professional who has knowledge and skills necessary to organize this kind of seduction, able to optimize abundance with access to quality commodities intended as an aesthetic experience of modernity: the pursuit of wealth and the duty of happiness through the consumption of satisfaction and comfort. But the

sustainability concept must be understood quite differently from that of sustainable development on a planet where 20% of the population consumes 80% of the natural resources.

In a system of commodities, the complementary dualism of ethic and aesthetic becomes a binary opposition that removes from the existence, along with all opposition forces seemingly antagonistic, all non-fictions: the non-beautiful, the not-good, the non-convenient, etc.. The static apparatus of legality completely replaces dynamics of legitimacy and ethics that

emerge continuously from a natural spirituality and sacredness.[…] The Greek concept of Techne, its applicability both to architecture and the practice of good governance of a city, had no distinction in technical aspects and moral guidelines. Behind the message of truth, of which art is a bearer, there is a natural ethic not captured in the visual experience. When art is in its peripheral position, splitted into decoration and structure, form and function, poetry and technology, it cannot make an impact on the viewer which cannot be guided but by the isolated and attractive pole of aesthetic.

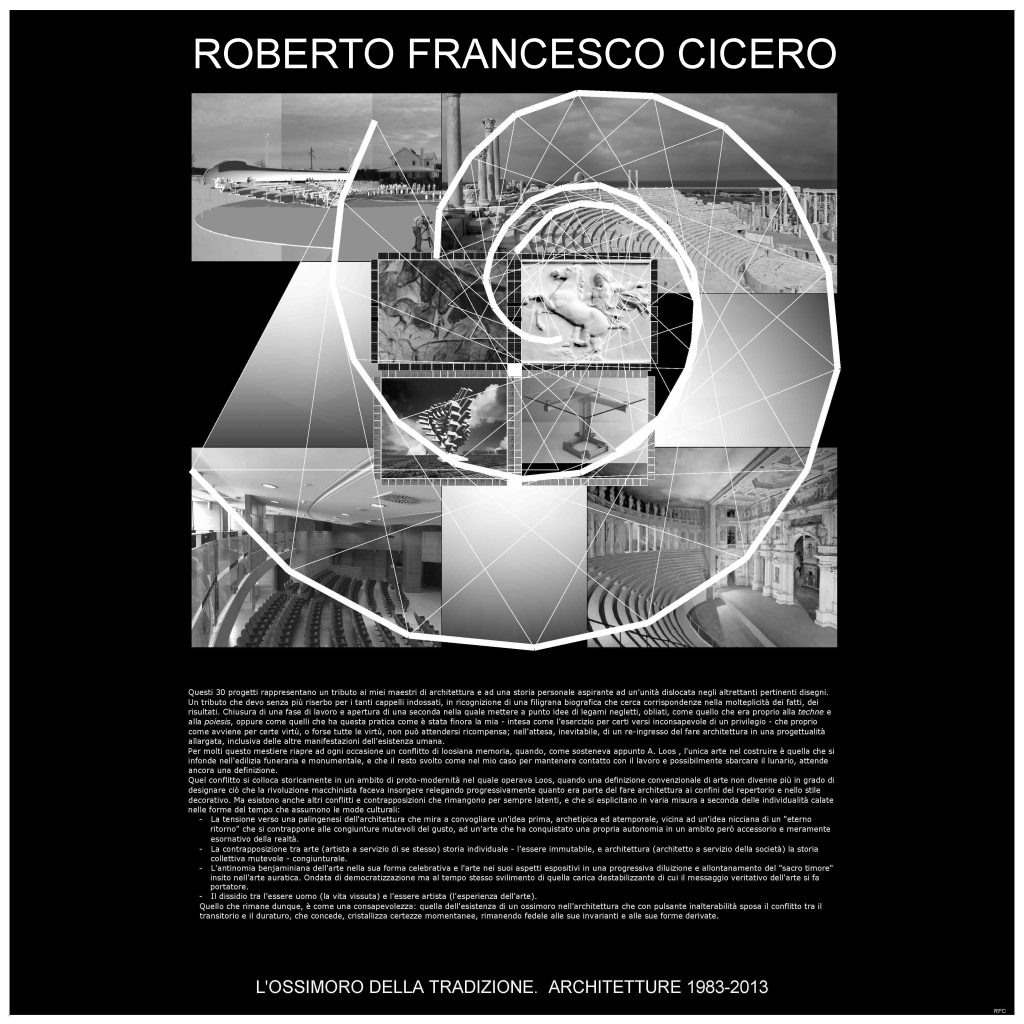

The reflection on permanencies and presences in history is the central topic in “The Oxymoron of Tradition” and linked to discourses on cultural heritage commodification held in the first book “Dal Palladio al sacco di Baghdad.”

Excerpts from “The Oxymoron of Tradition”. Architecture. 1983-2013.

[…] acquiring a notion of non-coded sustainability, moving to a vantage standpoint that eludes a dual form of dismissive naivety: the exaltation of technology with the claim of going beyond that of which there is no longer memory, and the opposite one which is under the illusion on the capacity of man, and of those ideological constructions called “man” and ” individual”, to dominate and drive it. (Emanuele Severino 2003)

[…] How should history be present and absent in contemporary architecture? How is it present dodging the postmodern solution that borrowed styles and references from the past, or absent, devoid of those symbols the unlimited growth paradigm and the third millennium economic agenda pursue within a dazzling scheme of hedonistic sustainability.

[…] “Lethe and Mnemosyne.”

The presence of history whether in a work of architecture or a work of art, is flanked always by another “narration”, unavoidable, contained in the microcosm of our personal lives. It presents another consonance with a parallel coplanar plot, but more contracted. It reveals this other presence as inevitable as history, but more corporeal: the narrative that is proper of autobiography. Every present in which our work can find its completion, is a mixture of what we consider the past and what we consider the future, shreds of reality that western nihilism considers respectively as no longer existing and not yet existing, thus as nullified events. This indissoluble union of memory and oblivion is like the amalgam of the two waters of Lethe and Mnemosyne: the myth of the river of memory and the river of oblivion. They are merged together in that eternal present moment which is the current time as both narration and prediction simultaneously set. It is narration as an act of memory, (our way to adhere to reality) and it is prediction (its

opposite) as an act of oblivion, something opposite to memory as a door to imagination. This process is similar to an ancient concept of truth (aletheia) as opposed to a logical truth based on the notion of “adaequatio rei et intelectus”. Truth through an act of revelation, by removing the veil provided by the oblivion, a remembrance process through a simultaneous pause of the imagination flow in order to disclose an event that gives with the same act by which it takes away.

[…] There are ideas, nihilistic ones, the western civilization encourages ab illo tempore in order to keep the world system going, in other words, paradoxically, to keep the state of affairs from moving and drifting apart from accepted truths taken for granted as the natural order for good in the absence of an ultimate truth. A branch of contemporary philosophy which finds its roots even further back in time, tells us that the problem has arisen, the problem of the West and the threat of its decline, with the faith after Plato, that things can come from nothing and return to nothing; with the certainty of becoming rather than in that of being.[…]

[…] Every work of mankind is “already there”, everything, every act of man is in attendance, every objective is already accomplished, eternally oscillating between presence and absence, decayed and renovated, old and new. The oscillation is an alternation of opposites that come in gradually slight variations; it is not the binary opposition of creation and destruction. The wood is not transformed into ashes, but it leaves, by remaining always equal to itself, its place to ashes. An appearing and a disappearing of “eternals”, perpetual beings exchanging places into single events.

[…] “Practicing, to some extent unaware, a privilege, a reward in itself that can eventually enlighten the Architect’s work, demands steep ascents, or else incurring the effects of Plato’s ontological condemnation of Art — source cause of a thin line– that a recognition of the Western cultural heritage through places, institutions and politics retrieves along an historical route unraveled across different episodes far apart in time and space.

[…] The commodification of Palladio’s cultural heritage began with a number of significant events : the acquisition of Palladio’s drawings and their handling by the court architect Inigo Jones, the divulgation of Vitruvius and the 4 books of the Venetian master, a disjointed aesthetic experience following the adoption of the word “Delight” as a translation of the word Venustas in Vitruvius principles of architecture, which opened doors to an entirely hedonistic version of architecture. The subsequent “export” overseas of that cultural heritage. That line closes itself in a circle with the break-in

into the archaeological museum of Baghdad and with the looting of Iraqi cultural heritage. In the historical perspective from which these events can be framed , that thin line appears as a thick steel tendon, although curved, when linking together Nietzsche’s reflections in the second of the four ” Untimely Meditations “, Adolf Loos’ “Ornament and Crime ” and Guy Debord’s concept of image as the ultimate form of reification.

[…] “Probing the nihilism embedded at the cultural and spiritual core of the 3rd millennium, refines a foundative means for understanding the state of things, far from a cutting-edged mere design tool, new-fashioned yet unsuitable to imagine and nurture social reforms aimed at forming a differently oriented professional figure, not comfortably placed at the end of the production chain where already exploited resources are dispersed, capable of providing advocacy actions for the community and the environment, antagonistic to a regime of hedonistic sustainability.”

A note about the author. Curve: Time in balance.

By Jani Scandura, Associate Professor.

Department of English

University of Minnesota.

Born in Tripoli to Italian parents and trained as an artist, Roberto F. Cicero is an architect and designer who has worked in Europe, the United States, North and East Africa. Returning to Rome as a teenager just before the Libyan revolution, RFC studied with architect Adriano Gentili and subsequently architecture and theory at the University of Rome “La Sapienza” under Bruno Zevi (1918-2000) Luigi Pellegrin (1925-2001) and

Born in Tripoli to Italian parents and trained as an artist, Roberto F. Cicero is an architect and designer who has worked in Europe, the United States, North and East Africa. Returning to Rome as a teenager just before the Libyan revolution, RFC studied with architect Adriano Gentili and subsequently architecture and theory at the University of Rome “La Sapienza” under Bruno Zevi (1918-2000) Luigi Pellegrin (1925-2001) and

Maurizio Sacripanti (1916-1996). Neither Pellegrin, a proponent of European organic architecture, nor Sacripanti, an avant-garde integrationalist thinker and designer, was enamored of the neo-rationalist Tendenza movement that dominated Italian design and architectural theory in the 1970s, but sought a different relationship to and through architectural history. In contrast with the strict formalism and archetypal simplicity of Giorgio Grassi, for instance, who referenced reduced classicist forms in modern materials and emphasized the situatedness of rectilinear shapes in space, Pellegin and Sacripanti, each

in his own way, foregrounded the interrelationality of time and space and to the centrality of content over form, movement and relationality over rational and mechanical code.

Shaped by his teachers, but also by an even more far distant cultural heritage related to his adolescence spent in Tripoli, with the fraught legacy of futurism and white rationalism of North and Eastern Africa Italian colonies, RFC’ work resists the neo-rationalist sterility and the citational quality of postmodern design as well as an aestheticization of ecology, in order to

imagine anew a contemporary architecture that retains a conceptually rigorous connection to history.

RFC’ professional experience is a rare combination of skills linked to his variegated/interdisciplinary portfolio of work going back over 30 years and spanning across 3 continents, where, along with typical architectural assignments, have merged industrial design, interior naval design for cruise ships, and his long worked consulting engineering experience with public entities in areas of cultural diversity administered by governing bodies of International Cooperation. The latter practice in particular, crossed by

moments of great synthesis of economic and technical instances within a debate with local cultural and environmental factors, is responsible for his radical approach. RCF’ “actions” with Systems For Living not-for-profit professional affiliation, oppose the “Society of the Spectacle” automatic “recuperation” processes (Guy Debord) and reform an idea of development

together with a conventional notion of art and architecture, distancing himself from a hedonistic response to sustainability demand given by either the industrial production or the third millennium professional and business world.

His work represents a series of efforts to think through classical problems using contemporary tools. For example, RFC’s designs for “Libra” table and his proposed “Labor” sculpture represent two efforts to consider the concept of balance in an asymmetrical shape. After completing Libra he summed up his work and realizes that Phidias’ famous bas-relief of “The cloacked horsemen” at the Parthenon, not as a formal precursor, poses the underlying

question, one that Phidias seemed to have answered without the aid of contemporary mathematics or an understanding of gravitational pull: how can a physical body maintain its balance while in motion? His design then toys equally with the question of stability and movement, of that which cannot fall, but seems about to. This then is the proposed monument, which references Rationalist ideals of labor but which allows for the possibility of

mobility that destabilizes the threat of rigidified and monumentalist doctrine.. It heralds labor while making present the threat of such a heralding.

A similar self-consciousness is embedded in RFC’s design for the auditorium “Sala Tirreno” inside the Giunta regionale del Lazio head offices in Rome. His charge was to design an amphitheatre and this became the occasion to question architectural type not as image or ideal nor even as Guilio Carlo Argan writes, as “as the idea of an element which should itself serve as a rule for the model,” but for the perceptive problematic for which the type serves as a momentary response. If every building carries with it the residue of the experience of forms already accomplished in projects and buildings, as Argan points out, then, RFC asks, is it possible to acknowledge architectural type in a way that is not merely parodic citation. He notes he discovered the parallels between his design and Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico only after the construction had been completed.

RFC’s fourth book “The Oxymoron of Tradition” was published in early 2014 and presented at the University of Rome “La Sapienza”. A new edition of his “From Palladio to the looting of Baghdad” is being published by La Caravella Editrice and delivered in October 2020.

Jani Scandura